Our Most Recent Medical Malpractice Trial

To Read The Full Article, Click Here

In September, we tried a medical malpractice case in Androscoggin County. After selecting the jury and three days of witness testimony, the case settled for a confidential sum.

Factual Summary

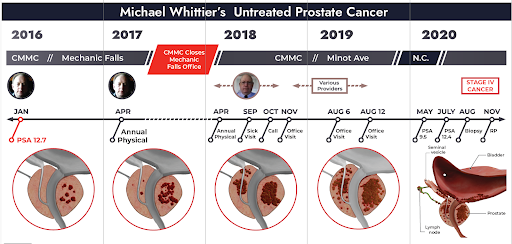

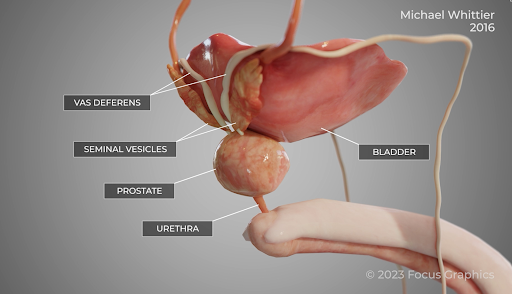

The case involved a more than four-and-a-half-year delay in diagnosing our 48-year-old client’s prostate cancer. The evidence presented at trial showed that the defendant primary care provider had the results of a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test for our client in January 2016, which was grossly abnormal and suggested a probability that he had prostate cancer. However, for a variety of reasons, nobody at the doctor’s office acted on the test results or communicated them to our client. From that point forward, although our client continued to receive medical care through the same medical corporation over the next four and a half years, nobody acted on the test results to refer him to the appropriate specialist for further work-up and treatment of his prostate cancer. By the time he was finally diagnosed with cancer more than four and a half years later, it was Stage 4 and had progressed outside of his prostate to his bladder neck, seminal vesicles, and one pelvic lymph node.

The “Blame the Patient” Defense

The primary liability defense in the case was to blame the patient. The defense argued that at an office visit for a physical exam one year after the elevated PSA test, the primary care doctor informed our client of the elevated test result and ordered a repeat test. The defense argued that our client failed to go for the testing, as ordered, and never reported the elevated PSA test to subsequent treating medical providers.

The “Delay Didn’t Matter” Defense

Additionally, the defense retained a nationally recognized expert in prostate cancer, Dr. Matthew Smith, MD, a medical oncologist from Massachusetts General Hospital who also serves as a professor in oncology at Harvard Medical School, to testify that the four-and-a-half-year delay in diagnosing our client’s cancer did not change his treatment or prognosis. Dr. Smith based his opinion on the fact that our client’s PSA levels were approximately the same in 2016 as when he was later diagnosed with cancer in 2020. According to Dr. Smith, the stable PSA meant that the cancer had not grown or spread appreciably over that time, meaning that it had likely already spread outside of the prostate capsule by 2016, and thereby would have required the same approach to treatment had it been diagnosed then.

Client’s Final Outcome

Even with the delayed diagnosis, our client received a prostatectomy followed by radiation and hormone deprivation therapy. He now has an undetectable PSA with a likely cure of his cancer. In other words, both the defense and plaintiff causation experts agreed that our client will not “more likely than not” die from prostate cancer.

Summary Judgment Motion

One potential challenge for our case related to Maine’s three-year medical malpractice Statute of Limitations. By the time the client came to us with the case, it had been more than three years since the medical care which had occurred in 2016 and 2017. In fact, the only office visit in which we were able to prove negligence within the three years prior to filing the case occurred in September 2018. Moreover, because the defendant medical corporation had closed our client’s primary care office and transferred him to a new provider in another office, the PCP who treated our client in 2018 was a different PCP from the doctor who treated him in 2016 and 2017. The defense filed a motion for summary judgment, arguing that the “continuing negligence” doctrine established in Baker v. Farrand, does not apply where the acts of negligence were carried out by different individual doctors. As we discussed in a prior column, the Court denied the motion for summary judgment on the grounds that the “continuing negligence” doctrine applies to “medical providers,” and the Maine Health Security Act defines “medical providers” to include health care corporations, not just individual personnel.

However, although we defeated summary judgment, it remained a jury question whether we could prove negligence relating to the September 2018 office visit.

Causation Standard for Last Act of Medical Negligence

Because it remained a factual question for the jury to decide whether there was “negligence” in September 2018, the question arose (and was subject of motions in limine) as to the causation standard for this last act of negligence which provided the basis to capture all the preceding negligence under the “continuing negligence” doctrine. Of course, it seems self-evident that whatever the specific causation attributable to this “last act,” the plaintiff would not be required to prove that the negligence of that date alone caused all the harm alleged. If the last act caused all of the harm, then there would be no need for “continuing negligence” to begin with. In Baker, the parties had stipulated that the last act caused “negligible or indeterminate” harm. Accordingly, we argued that with respect to the last act, we were required only to prove that it caused some additive harm that need not be more than “negligible or indeterminate” in quantity. The Court agreed that Baker necessitated a relaxed causation standard for this last act of negligence, although the precise language of the jury instructions had not been finalized by the time of the settlement.

Pre-Trial Negotiations

Before trial, the defense filed an offer of judgment at $2.5 million. Shortly before the trial, they increased the settlement offer to $3 million. We rejected those offers and took the case to trial because our data studies indicated that the case had a higher value.

Big Data Analysis

In preparation for the trial, we worked with a consultant to perform a “big data” analysis of the case. This involved preparing detailed summaries of the plaintiff and defense positions, replete with video of deposition testimony, exhibits and demonstrative aids, and presenting the case to almost 500 focus group jurors or reviewed the information and completed a detailed survey online. The data study provided us with a “win rate,” meaning the percentage of the time we would likely win the case at trial. It also provided us with a range of likely verdict values depending upon what we asked for in damages. Finally, the data study assisted us in profiling jurors that would likely be favorable or unfavorable for our case.

The data study was enormously helpful in providing an objective way to value the case for settlement. It told us that the $3 million pre-trial offer was not a reasonable valuation for the case. We provided the data study to our clients so that they could also benefit from making informed decisions about settlement of their case. We also provided the top line results of the data study to the risk manager for the defendant, to help educate him on the defendant’s potential exposure. Although this did not produce a resolution at that time, it likely contributed to our ability to resolve the case mid trial.

Attorney-Directed Voir Dire

Pursuant to Me. R. Civ. P. 47, our trial Justice permitted each side the opportunity to conduct attorney-directed voir dire of the jury panel. The Court first randomly selected twenty-five jurors to sit in the jury box. The Court then permitted each side the opportunity to question jurors in the box. In questioning by plaintiff’s counsel, several jurors expressed skepticism or unwillingness to consider allowing damages for things like emotional distress or pain and suffering. In questioning by defense counsel, one juror revealed that she had strong feelings about medical malpractice that would make it impossible for her to be fair to the health care providers. Following the oral questions, each side presented cause challenges, and the Court excused several jurors for cause after determining that they could not be fair and impartial jurors in the case. The parties then exercised their peremptory challenges.

In addition to being able to effectively target jurors whose answers indicated they had anti-claimant bias, our data study allowed us to rank each juror based upon their answers to questions in the supplement juror questionnaire and attorney-directed voir dire. For example, we learned from our data analysis that jurors who had personal knowledge or experience with prostate cancer were significantly more likely to vote in favor of the plaintiff. Thus, a juror who indicated he or she had some familiarity with prostate cancer received a “+1” point on our rating system. In all, we rated jurors positively or negatively in about ten different categories, each of which was a statistically significant predictor of how they would vote on either liability or the amount of damages.

Framing the Case for Trial—System Failure

In terms of our case frames for trial, we attempted to keep it clear and simple and to emphasize the larger system failures that went beyond the actions of any single medical practitioner. Although, perhaps, someone could excuse one individual doctor missing a single test result, what was not excusable was the lack of systems and practices in place to ensure that patient test results were reviewed or communicated to the doctors who needed that information to care for and treat the patient. At trial, we utilized a timeline (see below) that encapsulated the case on a single board and emphasized the long period of delay (more than four-and-a-half years) and the many missed opportunities that the defense had to identify and fix the problem, and act upon the test results, over those many years.

Expert Witnesses, Trial Animations

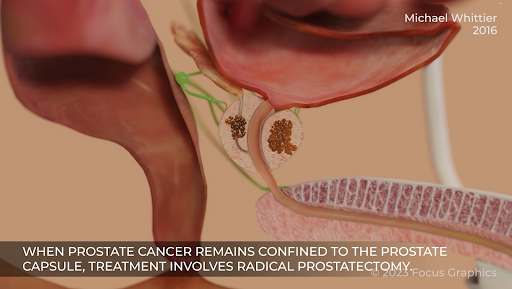

On the third day of the trial, we presented our liability and medical causation experts. Both experts did an excellent job of communicating their opinions to the jury. In order to assist our causation expert (a urological oncologist) in presenting his opinions, we developed and played for the jury two video animations (see screenshots below). These animations depicted how prostate cancer grows and spreads over time, and how early diagnosis of prostate cancer allows for a complete cure with removal of the prostate (a prostatectomy).

Case Settlement

After the third full day of trial—and with just a single remaining witness in the Plaintiff’s case in chief—the case settled for a confidential sum. The thought and careful preparation that went into the case helped us to achieve this great result for our clients.